The newspaper’s front-page headline read: “Irresponsible Dad to Blame for Tragedy.”

Fortunately, the headline was only in my mind’s eye. I was leading my wife, daughter, and son along a trailless, steep slope. The surface was slick with fresh snow and hailstones. We were amidst heavy rain and sleet. Clouds of mist rolled through the adjacent canyon obscuring visibility.

We were navigating the steep, trailless Roell Creek drainage in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. I should have known better; this was the second time.

Mary and my first trip in the San Juans, accompanied by our mild-mannered friend Dave, had occurred twenty-one years earlier. While Mary and I lived in Tucson, backpacking friends had described Colorado’s San Juans as the Holy Grail of mountains. We had climbed peaks in Southern Arizona, but the highest was Mt Graham’s 10,724-feet, an elevation not much higher than some San Juan trailheads.

Dave, Mary, and I hiked to 11,620 feet at Moon Lake in the Weminuche Wilderness Area, Colorado’s largest at 500,000 acres. We were greeted by thunder, lightning, high winds, and a downpour. I was running about frantically, looking for a camping spot. We lived in Southern Arizona. We were not accustomed to this. I pointed down by the lake. Weather, fatigue, and hail led Dave to uncharacteristically snarl at me. “That spot is sleazy as hell,” (the only four-letter word I heard from him during five years of acquaintance.)

Our sleeping bags and clothing were wet by the time our tiny pup tents were erected. Our tent flapped against our bodies. We were miserable. Welcome to the San Juans!

Our sour moods and anxiety shifted to enchantment when the clouds lifted. Slopes of talus intermixed with willow rose to snow-covered ridges. Sun-yellow dogtooth violets surrounded our tent. Magenta split-leaf painted cup flourished along the lakeside. Swampy areas showcased pink elephantella and creamy marsh marigolds. My outlook improved even more in the morning when I found the lake full of hungry brook trout. I caught enough for breakfast.

After a layover day with intermittent inclement weather, we hiked an off-trail route over an unnamed pass and arrived at Flint Lakes under threatening skies. We were wary, but the next day dawned still, clear, and blue. The fishing was good. I caught my first cutthroats.

I was enthralled and proud. After four nights in the wilderness, we considered ourselves experts. We perused our map and guidebook to select the next challenge. Dave and I noticed two lakes, only a few miles from the unnamed pass we had just traversed. Their names were Hidden and Lost. I wonder if it would have made a difference if they had popular names such as Bear Lake and Blue Lake. I suspect it would have. Anyway, we were intrigued, particularly because our guidebook (Gebhardt p71*) called them nearly inaccessible. Wouldn’t it be great to go there someday, we said.

Later in Tucson, I described our trip to a friend who had once lived in Durango, close to the trailhead we had used to enter the Weminuche. This friend had worked at an outdoor gear store and said a co-worker had once been to those lakes. That was 1976. I did not forget the conversation.

Mary and I returned to the San Juans the following year—a year of severe drought. It was early June—usually too early for high country access. Again, we achieved Moon Lake, caught fish, and even watched “ice out.” We climbed the pass again, which we named Half Moon for a nearby tarn, and scrambled up nearby false summits—our first sojourns above 13,000 feet. Our trip was enlivened by my “blowing up” one of those early canister stoves causing our sixth anniversary dinner to be not just freeze-dried, but cold!

Amazingly, without any expectation or pre-conceived attempt to do so, we moved to Western Colorado later that year. The following spring, on a long weekend, Mary and I hiked up Vallecito Creek to near Chicago Basin. I followed the trail farther to view the confluence with Roell Creek. Lost Lake is up there, I thought, while also noting a steep, wild, and impenetrable canyon. But more backpacking had to wait. Pregnancies and children came next.

More than forty-five years later, reviewing my journals, I tallied that our San Juan excursions included seven backpack trips of four-six nights, at least as many of two-three nights, and frequent day trips or overnighters for climbing seven 14,000 feet peaks and as many for climbing summits exceeding 13,000 such as the spectacular Rio Grande Pyramid (13,821) and the remote Mt. Oso (13,684). There were also various nights in motels or cabins in Telluride, Ouray, Silverton, and Lake City used as base camps for hiking or cross-country skiing.

How fortunate we have been to live within two to three hours of this magnificent range! When hiking in the Pyrenees near the French/Spanish border, we found ourselves looking at the rock and sky and saying, this is like the San Juans. We said the same when we hiked in Denali National Park in Alaska and in Spain’s Picos de Europa.

When I think of the San Juans, my first thoughts are of talus rising into the sky; meltwater rumbling underneath. I see dark cliffs, wet and shining. The sky above and behind massive peaks is tumultuous with various shades of gray and blue punctuated by patches of white as the clouds prowl among the summits as if planning when and where to unleash the next bout of riotous weather.

Once it rained so much the trail alternated between being a rivulet and a series of deep pools. Marble-sized hail fell and clumped together, as if each pool held a glob of floating gray refuse.

Another time, two inches of hail flattened our tent. We endured so much rain on that trip, I reviewed our tents and clothing (by then we owned the best high-altitude equipment money could buy, not including four-season gear), and remarked, even the best gear fails in three-days.

And there was wind–worse on fourteeners. At times, we were so battered that the rustling and whacking of our jackets was deafening.

Nonetheless, I love the sight of lightning and the rumble of thunder while being so close to the sky. I was fishing one afternoon at Lost Lake. I felt safe in the sheltered basin as storm clouds swirled on the surrounding cliffs. I was watching the ridge above as I reeled in a spinner. Suddenly, a jagged bolt of lightning erupted from a cloud and struck the rocky surface. Simultaneous with the tremendous clap of power, a wisp of dust and smoke arose from the assaulted stone.

Besides the weather, I think of wildlife. We learned to appreciate the echoing whistle of yellow-bellied marmots and the strange awnnk of pikas, their mouths full of grasses as they scurried on and within boulder fields.

One evening, after climbing San Luis Peak and Organ Mountain, our 360-degree view revealed three separate large elk herds. Later that August night, we heard thumping. I peeked out carefully and a snow-shoe hare scampered back and forth through our camp. Now and then it stood still and stamped its feet. The thumping continued until we emerged from the tent and began preparing breakfast. Then, a curious fawn walked into our camp and began sniffing our gear. We named it Bambi, of course, until we realized hunting season was approaching. We banged pots and waved our arms, trying to instill sufficient fear of humans.

And there were birds! We saw White-tailed Ptarmigan each time we ascended Half Moon Pass. The nearly endemic-to-Colorado Brown-capped Rosy Finch was common, that is, if we were high enough that we might also see American Pipits performing distraction displays to keep us from finding their eggs tucked under a rock.

A Boreal Owl perched overhead one night at Kilpacker Basin. Hiking out from the Three Apostles, after climbing the easier two, I was delighted with how common were Wilson’s Warblers and Fox Sparrows. My favorites though, are White-Crowned Sparrows. I appreciate the radiant ivory of their summer stripes, but mostly, I love their songs. They sang constantly throughout three rainy days at Lost Lake. It was a sound so cheerful and stirring amid the mist and clouds that I could not help but feel fortunate to be there, no matter what the weather.

ICE LAKE BASIN

A favorite location was Ice Lake Basin, now a sad story. We completed a reconnaissance overnight backpack with my sister in 1984 followed by a trip with our children, then seven and nine, four years later. On that trip, I deserted the family for an afternoon and bushwhacked to Island Lake.

Visitors to Ice Lake usually hiked to Fuller Lake and the high thirteeners on its skyline, but I had seen Island Lake on the map. It was in the opposite direction, and apparently trailless. When I arrived, so many trout were rising it looked like a rainstorm. The tiny lake, with its small rocky island, was exquisite. I wrote in my journal; the opposite side of the lake was purple with showy daisies and yellow with composites as these colors perforated the green carpet of grass that flowed up the mountainsides to the talus and cliffs above. The next morning, I hiked over early and caught fat rainbows for breakfast.

(Island Lake, before discovery, 1990.)

We returned the following year for what proved to be a too early trip, too much snow. We managed to reach Ice Lake, but it was still frozen, not visible under the snow. Although dazzled by a pair of mountain bluebirds fluttering among emerging rocks; their azure blue stunning against the gleaming white, we had to descend to the basin below to find a campsite.

We set up the tents in a sheltered location just in time to be pounded by rain, hail, thunder, and lightning. When the storm ceased, we emerged into a beautiful, although damp, evening. Typically, I disdain fires in the wilderness, but that night we had a delightful time sitting with our children as we dried out, warmed up, and watched the darkness fall.

The hike out was memorable for the sturdiness of our children and their appreciation of the beauty: solitary fiery yellow alpine buttercups in open patches amidst the lingering snow, Parry’s primrose beginning to flash dayglo pink; the stalks having only one or two flowers with most buds yet to open.

We absorbed all of it: the powerful waterfalls in the canyon below, the slopes all around flocked with a fresh, frosty coating, the aspens just beginning to color; the yellow of the new growth more reminiscent of fall than spring. A male Wilson’s warbler flashed yellow and black amongst the fuzzy buds of willows—no leaves yet. We watched a flock of pine siskins forage on a steep hillside as if tiny rocks had come alive. An American pipit rose, spread its wings, and launched down the mountainside. White-crowned sparrows with their spring-bright heads sang everywhere. Four chipmunks raced and chased through the meadow—as if the grass itself was moving. High above, snow, mist and rain circled amongst the peaks.

Once we descended below timberline, beautiful clumps of pink-red shooting stars lined the trail. These are usually spent by the time of hiking season. We had never seen so many. I wrote: The kids did great. I still see them in their rain suits with their dripping packs. They appeared burdened and wet—and happy!

Four years later, we returned. No one else was camped at Ice or Island Lake, but the latter had been discovered: copious fish carcasses and bones, shoreline overly trodden and newly eroded, discarded fish line and other camping detritus. No fish were rising and I did not catch any.

It was twenty-four years before I returned to Ice Lake. I was invited on my granddaughter Zia’s first backpacking trip. Ann, feeling nostalgic, wanted her daughter’s first trip to kindle a childhood memory like hers. The change was unsettling. I stopped counting the number of people on the trail when I passed one hundred. Two men were packing holsters with sidearms.

At Ice Lake, we were fortunate to find a campsite. Unlike many high-altitude lakes, Ice Lake has room for multiple camps, even though the presence of two groups prevents any privacy. By late afternoon, the area was crammed with fourteen separate parties. Near dark, two more backpackers appeared. Where would they camp? I was shocked to watch them bushwhack through the vegetation on the lake’s trailless far side. They beat down and cut willows to pitch their tent. I was appalled, but worse was to come the next day.

We decided to have lunch at Island Lake. There is now a beat-down, wide, trail. No surprise there. I counted nineteen hikers ahead of us within a quarter mile of steep slope. Once we reached the lake, there were so many visitors, we opted to sit amidst the talus on the far side even though we had to hop rock-to-rock to prevent wet feet. We sat on boulders, spread out our lunch, and heard and then saw the drone someone was flying. The Ice Lake Basin I had shown my children was gone.

Most of the hikers were much younger than me—especially my granddaughter. What did they think? Did they have a sense of discovery like mine decades earlier? The phenomenon that each succeeding generation believes they are discoverers or believe “it has always been this way,” even though the experience has deteriorated, has been labeled generational amnesia. Due to the short lives of most humans, our species does a poor job comprehending the long-term. Old curmudgeons like me are needed to tell them how it was.

It was marvelous! The memories become a torrent in my mind. Such as the time we hiked up East Ute Creek, spent three nights with the Rio Grande Pyramid and La Ventana (the Window) on the skyline, and saw no one else, only elk! The kids performed a skit and sang camp songs. We tried to climb the Pyramid but, within five hundred feet of the summit, were chased off by an approaching storm.

We returned a year later (1991), approaching from the other side, via Weminuche Pass. It was dry. I hiked uphill looking for water. A mistake. All I found was a stagnant pool replete with elk droppings. It was now too late to hike to the clear streams below camp. We filtered, boiled, and added iodine, realizing how bizarre that some of the worst water we have ever used was from high in the San Juans.

The next day, we easily scrambled up the big boulders to the summit. The peak’s isolation yielded the magnificent view we expected. But then I was to recall a comment from Gephardt’s book, that the Rio Grande Pyramid seemed to collect severe weather. Immense black clouds were emanating from the surrounding valleys. We descended to our camp and endured a heavy downpour.

Typically, rain stops by early evening. We waited but it kept raining. Mercifully, the rain ceased as the sun was setting. Climbing from our tents we beheld a vividly colored rainbow rising behind a rocky 12,000 feet ridge. The ridge itself was pinkish orange in the alpenglow. The rainbow seemed to grow from it and vault into the sky.

When I awoke in the morning, I walked a short distance from camp to view the broad valley below Weminuche Pass. It was fairyland. A curtain of mist was blowing up the valley hanging above the vegetation in a wispy, curling band that climbed a few tens of feet into the sky. Each blade of grass and willow tip below the gossamer ribbon was coated with a film of water that sparkled as if diamond coated. Boggy locations were distinct as they emitted their own traces of mist and fog into the sun-filled morning. It was breathtaking. I ran for the rest of the family but, by the time we returned, the temperature and sun angle had changed. The effect was gone, but the memory persists. This is why I go backpacking, I thought.

CLIMBING FOURTEENERS

Unfortunately, backpacking in the San Juans also taught me about altitude sickness. My first session was on Mt Sneffels. I blamed my nausea and slight headache on having slept poorly. I climbed from Blue Lakes Pass rather than use the standard Yankee Boy Basin approach. There was no one else on the steep and loose route. Cliffs and blind turns were frequent, but I continued to find footprints, or I would have turned back. At last, I reached a solid ridge with the peak about 250-feet above. Despite copious exposure, the four feet wide ridge was solid with great foot and handholds.

From the summit, I viewed rainstorms in all directions, and a lot of people. I lingered for about 10 minutes.

Instead of descending slowly on talus, I glissaded on my backside down snowfields. Just above Blue Lake Pass I slid about two hundred yards. My speed increased dangerously but I was able to shift my boots more on edge and slowed down without tumbling. Trembling, I stood up. To my mortification, the back of my pants was in tatters and my wallet somewhere upslope. (Two years later, another hiker found its chewed up remains and mailed it to me!)

While descending from Mt Sneffels the nausea and headache vanished, and I forgot about them until two years later when I became sick on Wilson Peak. Perhaps it was because I was again above 12,000 feet or because I had climbed the last part anxiously while Mary waited below, having tired of the talus.

My head was throbbing when I reached the top, but the surprise was realizing that I had forgotten to eat lunch and found my canteens still full. My mouth and throat were so dry, I was unable to speak.

We had already set up a camp near an old hotel at 12,500 feet. (Those miners were tough!). A horrible night ensued. Rain and wind whipped the tent while I was tormented by a severe headache and queasiness. Whenever I would doze, I dreamed of the peak looming malevolently overhead while I slid downward on talus about to tumble over a cliff. I wrote, I felt so bad, I wished I had!

We packed in the twilight and were hiking by 6AM. Remarkably, as soon as we descended a couple of thousand feet, I recovered completely. After breakfast at a cafe in Ridgeway, I had a fine day.

That is how I learned about diamox for altitude sickness, which I used to significant effect when we climbed Sunshine and Redcloud, Ann and Adam’s first fourteeners. From Sunshine Peak we had a typical San Juan view: mountains marched into the distance in all directions. It seemed like we were walking on the roof of the world; the view only marred by the violent wind. I felt great although we were dismayed to find a small bulldozer tearing up the trailside creek as someone performed due diligence on an old mining claim. We discussed Edward Abbey and his book The Monkey Wrench Gang, and discovered on our return, that monkey-wrenchers had been there in the night—smashing windows and cutting hoses.

Our next mountain was nearby Handies Peak, an easy hike, with what one author called the best view in the San Juans. Initially, the hike passes aquamarine Sloan Lake, nestled under the imposing American Crags. On top, gazing southeast, the Rio Grande Pyramid dominates the skyline. As one makes a pirouette, there are the Needles and Grenadiers deep in the Weminuche, then Fuller Peak, Golden Horn, and Pilot Knob toward Silverton followed by Mt Sneffels near Ouray. To the North are Wetterhorn and Uncompahgre. Redcloud and Sunshine are in the foreground.

My favorite fourteener experience was when Mary and I climbed Uncompahgre Peak on a rare, still, and cloudless day. There is a 700-foot sheer cliff on one side, yet room for a football game on top. All around we could see other peaks we had climbed: Wilson Peak, Redcloud, Sunshine, Handies, and, as always, the Rio Grande Pyramid. We saw no one else the entire day, which enticed us to have extra fun at 14,000 feet. Is that possible anymore without creating a show for voyeurs? We remained for three hours, not the 10 or 15 minutes one usually has because of threatening weather and the number of people arriving.

I wanted to climb all of Colorado’s fourteeners but lost my passion for them on El Diente; the most difficult any of us attempted. Adam and I started from Kilpacker Basin. El Diente, as much of the San Juans, consists of rotten rock. At 13,500 feet, Adam hoisted himself onto a slab. It began to slide. We leaped out of the way, but both of us received a glancing blow. As we limped off the peak, I realized I had led us off the route. We were ~500 feet below the summit, but as we were to learn later, on the wrong side. We slowly worked our way six hundred feet lower before snow started flying. We completed our descent in mist and fog, never having seen the summit.

Determined, we returned a year later. With the previous experience and new intelligence from successful climbers, we attained the ridge below the summit—in heavy fog. We knew there was eight hundred feet of exposure but could only see ten-fifteen feet before the world disappeared into a wall of mist. We moved carefully, stopping at each cairn long enough to see the next one. It was eerie. Mist swirled at our feet. We knew the exposure would be thrilling, but we never saw it.

The cairns ceased at a small saddle. We ascended, but it was a false summit. We backed down, climbed up the other side, and found ourselves on top. How did we know? There was a summit register. There was no view. The mist changed to steady rain. Luckily, it was not an electrical storm.

After a few minutes of peering hopefully into the thick grayness—we might have been on a rainy seashore rather than a mountaintop—we carefully descended. For more than an hour, I observed that a slip or an unexpected loose rock would have caused a long, painful tumble. We could check off El Diente as having been climbed but we had not even enjoyed a view. Though we climbed other peaks, that was the experience when I lost my desire to climb lots of them. I decided canyons, especially the Grand Canyon, were safer and less crowded, but that is another story.

LOST LAKE

But what of the fabled Lost Lake? In 1992, with Ann and Adam still pre-teens, we accomplished an ambitious multi-day, springtime, backpack in the Grand Canyon. The trip had gone so well, that the goal of Hidden and Lost Lakes returned to prominence. I planned for the following August.

We now lived north of the trailhead we used for our earliest trips to the San Juans. It would take a day to drive around to the southern access we had used previously. Unfortunately, the closer, northern access, from the town of Silverton, required driving roads famous for jeep trips that attract travelers from all over the world. Our only car was a Nissan Stanza, a tiny, boxy, powerless station wagon with back doors that slid rather than swung open. As the trip would prove, however, it had two positive attributes, good clearance, and a small wheelbase.

The closest access was the road from Silverton to Creede. From Silverton, we would have to drive over Stony Pass (12,492 feet). The road description in 1992 was like today: High clearance, 4WD, and off-road vehicles are highly recommended for summiting Stony Pass. The road contains sometimes challenging terrain and can become very narrow in parts.

If we entered from the Creede side, which was a longer access drive, we would encounter Timber Hill. Friends told me our car would never negotiate this notoriously rocky and steep section. I decided to try Stony Pass. At the top, the car spun out, lacking the power to negotiate a final, steep turn. I backed up as far as possible and made a run at it—same result. I tried again. Ditto. Last chance. I had the family disembark and remove the four backpacks. Five hundred pounds made the difference, with wheels spinning and rocks flying, I reached the top. I noticed the temperature gauge was alarmingly high, but it is all downhill from here, I concluded.

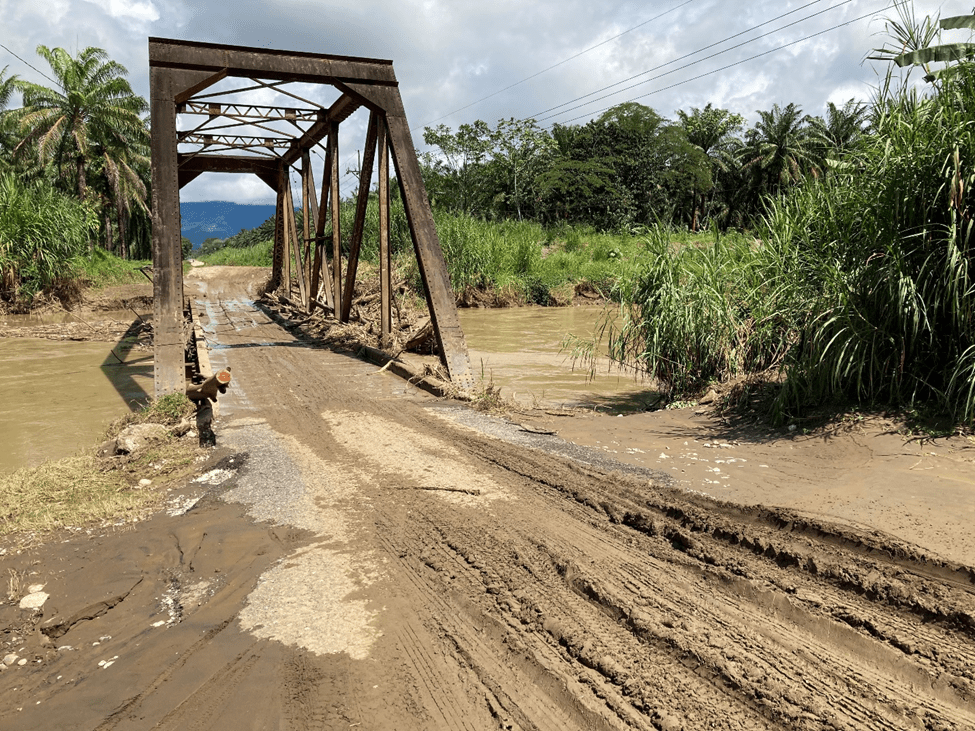

We reloaded, drove over the pass, and were faced immediately with a longer and steeper downhill turn on the other side. I knew we could never ascend Stony Pass from that side. There was no choice now but to continue to the trailhead at the abandoned mining area of Beartown. We would do the hike and worry about Timber Hill in a week.

First, however, we had to cross Pole Creek. It was not running particularly high, but we did not have a particularly adequate vehicle. I inspected the creek. We had no choice but to go for it. With water splashing along the running boards and up into the engine, we made it across. We drove as far as possible on the Beartown road and parked our little Stanza next to a cadre of Jeeps, Scouts, and Broncos. I looked at my watch. We had driven about twenty miles in two and a half hours.

We were not at the trailhead. After walking the jeep road for a while, I spied a good trail heading the right direction. After climbing three or four hundred feet, the trail disappeared into a patch of willows. We could find no sign of Hunchback Pass; our hike’s first landmark.

Maps indicated the trail had to be directly south, so compass in hand, I led us through the willows and intersected what I thought was the correct trail. It was not. We were further south than I expected. Instead of the Vallecito Creek Trail, we had encountered the Continental Drive trail and were going the wrong way. After correcting the error, we camped at Clark Lake, miles from where we had expected to be.

The next day, we completed the lengthy hike to Rock Lake passing West and Middle Ute Lakes with distant views of the Rio Grande Pyramid and the Window. At Rock Lake, the mountains greeted us with thunder. We retraced our steps slightly to camp in a flat sheltered area.

From Rock Lake’s shore, our self-proclaimed Half-Moon Pass and Peters Peak (13,122 feet) frame the view to the south/southwest. The Roell Creek drainage with access to Lost and Hidden Lakes is obscured. Distantly, to the Northeast, the skyline is dominated by the diamond shape of the Rio Grande Pyramid. I crawled into my sleeping bag with anticipation, Tomorrow! Lost Lake! In the morning, we methodically approached the hike one section at a time. Mary and I were exultant at Half Moon Pass, having returned to this remote location after 15 years. We viewed Moon Lake far below, where we had camped in 1976 and 77. That was to be our alternate destination if we found the route to Hidden and Lost too difficult. There must have been fifteen tents—a boy scout troop, perhaps. But we could see an achievable saddle between Mt Oso and Peters Peak. The Roell Creek drainage was just beyond.

(Saddle separating Roell and Rock Creek Drainages.)

After taking photos, we departed the cairned route and aimed for the saddle. There appeared to be a deep ravine in between, but no, once we approached, we easily traversed a shallow drainage until we beheld the rocky saddle above. We observed that with care, we could mostly ascend from one grassy spot to another. Two parts done! Well, let’s see what’s on the other side!

We peered down the Roell Creek drainage. These lakes are tough, I thought. We had just climbed from a campsite at 11,800 feet to a pass at 12,800. Then we descended five hundred feet and reclimbed to a saddle at 12,500. The route below was steep and rocky, but there were willows and grass patches in between.

What was discouraging was how far we had to descend. Lost Lake was on our left, as was a towering cliff. Next to the cliff was talus. A steep, tree-covered slope was apparent at 11,400 feet. Mary avoids talus; hence, the latter was our choice. We descended, as did the clouds.

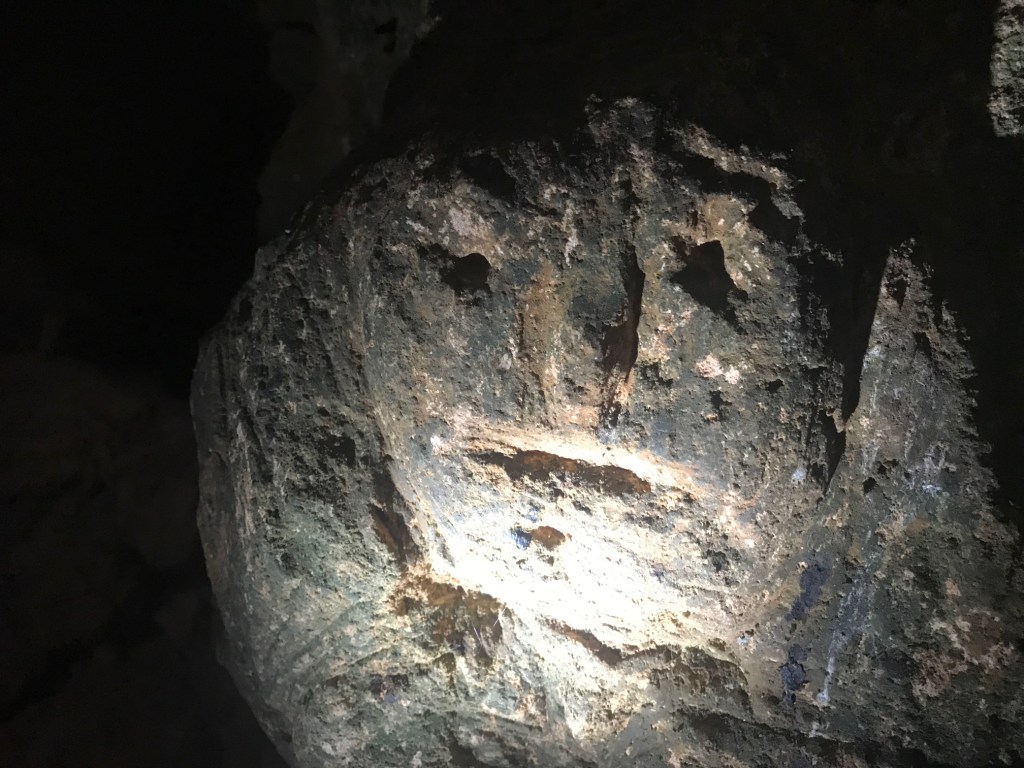

We all noticed a different ambience on the other side of the pass. It was pristine. No trail. No cairns. No one had removed lower branches from trees for campfires. It was primeval.

We climbed hand-over-hand, tree-to-tree, up the steep slope. It leveled out. There was a stream rushing through a wet meadow. We continued. Suddenly, over one more slight rise: Lost Lake! I hugged Mary and we shed tears as fifteen years dreaming about this lake washed away. So many times, I wondered while taking care of small children and during our sojourn in Missouri, would we even backpack at all, much less this?

Yet, it was raining. We set up our tents and climbed inside. I impatiently listened to the rain. It was not intense. I have waited fifteen years to come here, I thought. I am not spending it in the tent. I donned raingear and accompanied by Adam, went fishing. Those cutthroats hit everything, including an old, hammered spoon I had owned for twenty years and had never caught a fish. While we fished, hail fell straight down, creating a vertical splash as if the lake’s surface was covered with thousands of silver springs. Eventually, the sun broke through. The mirrored surfaces of the granite peaks glistened in the sunshine.

We had a wonderful time, but the weather never cleared, not the rest of that day, nor the next when we worked our way across a mile of talus to view bigger and likely deeper Hidden Lake. Wind and hail abbreviated our visit.

That evening, I told Mary I hoped to catch and eat fish before we left in the morning, but if the weather were threatening, we would leave quickly. She said, I hope it is an easy decision.

At first light, we could not see the peaks around us. The clouds lifted momentarily. Now we could see. Snow! We knew the trailless passes we had to climb over would be wet and slick. We were fearful of climbing so high. We decided to bushwhack down Roell creek.

We had to descend three thousand feet in less than 2 miles. It meant slogging through soggy woods interspersed with wet, slick boulder fields while it rained and hailed. There was quite a lot of deadfall, but the biggest problem was how slippery it was. We stumbled numerous times. I wrote later of Mary and her hatred for boulder fields and talus: Mary slowed the rest of us but really—how many women in their mid-forties did I know that could have done this? She did great-just slow and careful.

After four hours we reached the valley bottom where we encountered a swamp. We had to wade and though the rain had stopped; we were now even wetter than before. Of course, the rain started again once we intersected the Vallecito Creek Trail. It rained so hard; we gave up trying to ford creeks and just sloshed through them. Mary wanted to hike out, but I did not think we could make it by dark and I did not want to cross 12,500-foot Hunchback pass in stormy weather.

We stopped at Stormy Gulch, started a fire, and dried out. The kids sang camp songs, and we roasted socks. The next morning was bright and clear, and we routinely hiked to our car. As we approached, Ann said, oh, look there’s a marmot,” as one dashed away from under the vehicle. I thought this odd, but not troubling until I tried to start the car. I had plenty of battery, but the engine would not start. I peered underneath. I smelled gas but could not see leaking fuel. I asked Mary to try and start the car while I looked underneath. Gas spewed from the supply hose. Several inches of it were chewed. It was not reparable.

I learned later marmots chewing hoses and other undercar parts was common. According to the National Wildlife Foundation: No one knows why they do it. It could be that they are trying to supplement their diets–after weaning in early summer–with the crusty mineral deposits often found on engine parts.

We were stymied. Miles from a paved road. I looked at the torn hose and suddenly thought of our water filter. It had eight to ten inches of plastic hose. Could I use it for a splice? Remarkably, it was a perfect fit. I started the car. I was concerned because I had used all the tubing. How long would that piece of hose last?

Timber Hill was as steep and rocky as advertised, but our little car’s high clearance and small wheelbase saved us. By going slowly and carefully, I could maneuver around the big rocks and steep holes. I did little but ride the clutch and brake as we rolled downward.

It was amusing to see the incredulous faces of the riders and drivers as they passed us going uphill. It was Sunday afternoon in the middle of the tourist season. I must admit to feelings of superiority as we passed Texans (I presumed, if they were in rentals) in their Jeep Wagoneers, Ford Broncos, and Chevy Blazers.

It was late afternoon when we emerged onto pavement. I had planned to stop for a replacement hose but where on late Sunday afternoon? Nothing was open. We drove non-stop, straight home. We pulled into our driveway and unloaded the packs. Afterwards, the car would not start when I attempted to put it in the garage. The little plastic hose from the water purification kit had finally disintegrated.

We returned to Lost Lake five years later in 1997. I now owned an authentic 4wd vehicle and could drive to and park at the correct trailhead. This time we used the Vallecito Creek Trail and were able to hike to Rock Lake the first day and enjoy the entire hike. The trail is mostly under 10,000 feet. It was exciting to hike among so many peaks exceeding 13,000 feet and then view Sunlight and Windom which exceed 14,000 feet.

Rock Lake is attained via a four-mile ascent from the Vallecito Creek trail. As the trail climbs, the view to the right is of a gray cliff-face. Water rushes down at one point from the Annie Lakes, a name we enjoyed because of our daughter. The broad visage of Buffalo Peak looms over the ascent.

We endured hard rain in the early evening but woke to a clear morning. I again marveled at being on Half Moon Pass, thinking of that first time, now twenty years previous. As before, we avoided the talus approach to the lake and used the steep descent into Roell Creek valley. (The next two times I journeyed to Lost Lake, we climbed the talus and found it solid and faster.) By the time we arrived, it was raining and as my journal noted, it just kept raining. Fishing was interesting—time after time, the fish lazily followed our lures, but there were no strikes. Once, there was a brief flash of sunlight and suddenly all three of us had a fish.

The rain continued. Lost Lake is at 12,000 feet. Because of the difficult access, an early season trip is impossible because of snow, and by the time the snow melts, it is the rainy season. I had planned to climb Mt Oso but gave up the idea because of the weather. We could stand only so much tent time and often went out in the rain. There is a promontory that hangs over the valley and gives a wonderful view of the ragged skyline to the west—Sunlight, Windom, and others. One evening was beautiful as the clouds cleared and the peaks were bathed in Alpen glow.

We had planned to stay a fourth day, but everything was so wet, we decided to leave. Our plan was to fish for breakfast while Mary packed up camp. We planned to return to Rock Lake and depart through the Ute Lakes country, spending the last night at Middle Ute Lake.

About 1AM it began to rain and rain and rain harder. The inundation did not slow until after 5. At about seven, I unzipped the tent to a depressing sight. The fog was so thick, we could not see ten feet. Our gear was soaked. Our spare clothing had gotten wet through the packs. Even though our camping spot was on higher ground, it was now a bog. Through it all, White-crowned Sparrows continued to sing. I will always associate their cheerful songs with the beauty and sogginess of Lost Lake. There dee de de du dee up and down the scale just continued.

We had been determined to avoid Roell creek, but once we descended from the lake, the deluge began anew. Everyone agreed going higher with possible snow on the exposed passes was a bad idea. With a heavy feeling of déjà vu, we fashioned walking sticks and began to descend the Roell Creek drainage again.

I did not want to subject Mary to the talus-laden rocky ridge top we had traversed the first time. The deep green shown by the topographic map for the slopes of the canyon deceived me into believing they were uniformly tree-covered. Traversing a forest with deadfall would be difficult, but I reasoned that we would avoid the boulder fields that had slowed us so much the first time.

There were trees—here and there. Mostly though, I had led us on to loose talus on steep slopes, with occasional exposed cliffs—much worse terrain than the previous time. We slipped frequently, but no one fell. We could not see far enough ahead to select the best route. The steep hillsides were one thing, but we had to cross ravines where all the rock was unstable. We had been above this the last time we departed Lost Lake. Because we had accessed the slopes while lower in the drainage, attaining the ridge top would have entailed a steep climb up loose talus. No one wanted to do that, so we continued to traverse slowly, never walking on level terrain, as the hail, rain and sleet continued. This is when I began seeing in my mind’s eye newspaper headlines about my family’s tragedy.

Finally, we achieved a downward incline heading west. Finally, each foot could be at the same elevation as we traveled. What a relief! Later, I wrote in my journal: no matter what the weather, if I go back, I’m never descending Roell creek valley again. We still had to wade thigh deep through beaver ponds, but at least the danger of falling was past.

Six hours after we started, we collapsed at the first flat area we found once we intersected the Vallecito Creek Trail. We built a fire as the weather cleared. We had two mostly dry sleeping bags and one mostly dry tent; the larger one that had been shared by Ann and Adam. We spread out anything partially dry for a ground cloth, and the four of us huddled together sharing the two dry bags as blankets.

The next morning, we had ten miles to hike to the car. We had been unable to start early because of fatigue and wet gear. We hiked slowly. There were occasional memorable views. The clouds blended into the peaks, never lifting completely, giving the appearance that the rocky summits kept rising as if they were 20,000 feet high not 13,000.

It rained all day, but we were able to cross Hunchback Pass in drizzle and mist rather than thunder and lightning. On top of the pass dark skies closed in. We skipped a planned stop for cooking supper and hurried to the car.

At our vehicle, I was relieved to see no signs of a marmot. We drove out of Beartown and arrived at Pole Creek where a couple was waiting with an ancient International Scout. With all the rain, the creek was roaring. I would have turned around if we had been alone. The couple thought the same. They had not wanted to ford the raging creek without help nearby. They had a rope with which the driver believed we could pull out a drowned vehicle. After explaining, they jumped in the rusty old Scout, splashed deeply, and chugged out the other side in a cloud of steam.

The driver stopped and threw up the hood. He yelled back he had bent his fan blade. I learned later that as I was yelling back and forth with him, my family, after seeing how the Scout had fared, had agreed, I would never try it. I was already on my way when they began screaming. For a second or two it was easy and then the front end plunged into a trough. There was a frightening moment as water splashed over the hood and on to the windshield.

But I could feel the rear wheels push the front ones from the hole and then the front wheels pulled us out. We had made it! Steam was everywhere. Water was inside our vehicle, but we had no damage. Not so for the poor folks in the Scout—their bent fan blade had punctured their radiator. The leak was slow. They had extra water containers and said we should go ahead. They were confident they could slowly make it to Silverton.

We arrived in Silverton about 8:30. Starving, we entered a restaurant. The kids were embarrassed by our condition. I had no other clothes or shoes, but no one said anything, and we ate heartily. We arrived home after midnight. I wrote later: It is hard to close the book on a trip like that. Was it fun? Was it an ordeal? Would I do it again? It was wonderful to be in the mountains and be able to succeed. But, next time, I want sunshine!”

I returned twice more. The next year, I returned with Adam and one of his swim team members. Adam’s friend, although in good condition, was not accustomed to backpacking. He struggled and did not appreciate being watched over by the Guardian (13,617 feet), the rest of the Needles, the beautiful little cascade falling from the Annie Lakes or the beauty of Peters Peak.

(View from the Vallecito Creek Trail.)

At Rock Lake, we learned the trip would not be without incident. Due to confusion with gear having been lent and re-packed, I did not have my tent. The three of us had to cram into the small tent the boys had planned to share. The only way we could fit was with six-foot-three 200-pound Adam in the middle. He slept soundly but tossed and turned relentlessly. It was a long night. Why did I not sleep outside? It was raining!

In the morning, we headed up the now familiar pass with all the customary sights: Rio Grande Pyramid, the Window, then Moon Lake and all the mountains beyond. This time we scrambled up and over the talus without descending below tree line and saved an hour or more attaining the lake.

(Half-moon Pass with Rio Grande Pyramid in the far distance.)

Unlike his friend, Adam stayed with me stride for stride, never complaining. At the lake, I lifted his pack and could not believe it. He had carried the tent, their food and nearly all their gear just to stop his friend from complaining. What a powerful son I have, I thought.

Fishing was lousy this time and frustratingly, it began to rain in the early evening. The boys retreated to the tent to read. Not wanting to cram into the tent, I tried to find places under vegetation to read and keep dry. Ironically, I was reading Van Dyke’s classic The Grand Canyon of the Colorado. Reading about hot and dry country did not help. I became too wet and had to join the boys inside.

It was another long night, but the morning was bright and clear. I wanted Mt Oso. I took breakfast bars, homemade logan bread, and started early. I had seen a crack on the southeast side of the basin that accessed a definite chute leading up to Mt Oso’s southeast ridge—the proper route according to my thirteeners guidebook.

As I climbed, I was reminded of the adage: A rolling stone gathers no moss—or lichen either. None of the rocks I was climbing on had lichen—they were constantly, albeit slowly, on the move. I would perch on a boulder or slab large enough not to slide with my weight added. Then I would look for another and sprint spider-like over smaller and lighter rocks until reaching the next one large enough to hold me. I would catch my breath and repeat.

As I continued upward, the route consisted of one-foot-diameter- sized rocks at the angle of repose. I crawled, slipped, stood up, slipped, walked, and slipped. It was the longest stretch of talus I have ever done where the rocks were comparable size, and the angle of the slope did not deviate. I was relieved to reach the summit ridge.

The ridge dropped off shear on the east and I realized I had been viewing Oso’s profile when I had been at Moon Lake. Although steeper, the ridge’s foot and handholds were solid, and I scrambled to the top in minutes. The summit was about twenty-five feet long and two-to-four feet wide.

I enjoyed the beautiful morning from the top for more than an hour. The view encompassed the vast meadows of the Ute creek country backed up by La Ventana and the Rio Grande Pyramid. There were the usual familiar peaks for me to pick out: Sneffels, Redcliff, Uncompahgre, and El Diente. I love this country!

The descent was slow. I was constantly bracing, often relying on the friction of the seat of my pants. The chute to Lost Lake basin was treacherous. I could hear water running under as I slid, sat, and walked down. It had taken slightly more than two hours for the climb and an hour and a half for the descent. I had climbed Mt Oso! —something I had thought of since 1977 and had missed on two previous trips to Lost Lake. I was exhilarated.

The weather remained fine. (We were due!) I was able to sleep under the stars at 12,000 feet. With continued clear weather, we could return the way we came.

As we bypassed the Lost Lake drainage on the talus and worked our way down to Roell creek. I realized attaining the pass over to the Rock creek drainage was formidable. Our choice to depart via Roell creek on those other trips was not unreasonable. In retrospect, the bad choice was to depart on such harsh weather days. We should have simply hunkered down.

After dropping into the Flint Lakes’ drainage, we stopped for lunch. I wrote of the view: a dark gray rain cloud is hanging over Half Moon Pass. Immaculate white clouds are billowing behind, shimmering in the sun. Below lies Rock Lake, its rippling, sun-dappled surface appears as if paved with diamonds. Mt Oso and Peters Peak stand to the near west with the Needles extending to the far west. Turning the other way, I gaze at La Ventana and the Pyramid. The way the clouds and light play all around is mesmerizing.

The trail, however, was awful, badly braided and chest deep in places. It was not full of water now, but water erosion was the probable reason there were so many parallel trails. How bad will this be when Adam is my age? I thought. I suspect it will be a wide, barren, muddy slope. Our walk to West Ute Lake was a long one, but fish were rising, and we soon caught several. I slept outside again, but howling winds contributed to a long night.

Fifteen years later, I made my last trip to Lost Lake. I was sixty-four and recognized that my time for such trips was dwindling. My companions were Adam and my son-in-law Ryan. I enjoyed not being in charge. Let the two strong young men lead! The weather was pleasant. On our first evening, a Bald Eagle soared over the ridge above and with a sudden dive, plunged into the lake for a fish.

(My last view of Lost Lake.)

On our final afternoon, we hiked to Hidden Lake. Were there fish? We had never had the opportunity to find out. I quickly had a strike, but the fish threw the hook. Meanwhile, Ryan caught the brightest orange trout I have seen. It had almost no fins—apparently, they were worn off against the rocks. The fish was ancient. How long since Hidden Lake had been stocked? How often did anyone catch a fish from it? Hidden Lake does not have an outlet stream for spawning; this fish appeared prehistoric. That evening, Ryan expertly cleaned and baked the fish on a bed of coals. I have eaten many trout, none more flavorful.

*Gebhardt, Dennis. A backpacking guide to the Weminuche Wilderness in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. Basin Reproduction and Printing Company. April 1976